How Many Animals Are Lost To Loss Of Habitat Last 25 Years

Christopher N. Johnson

School of Natural Sciences and Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, University of Tasmania, Hobart Tasmania 7000, Australia.

I of the largest effects of humans on the natural world has been to raise the rate of extinction of species far in a higher place natural levels. This began many thousands of years agone, and as a result the human being-caused loss of global biodiversity was already pregnant before the modern era. Now, the extinction rate is accelerating, biodiversity is in rapid decline, and many ecosystem processes are being degraded or lost.

ane. History of homo-caused extinctions

The effect of humans on global biodiversity first became meaning as modernistic Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to occupy the other continents. Between well-nigh 60,000 and ten,000 years ago, a wave of extinctions of giant animals – mammoths, basis sloths, giant kangaroos, and many others – followed the inflow of people in Eurasia, Commonwealth of australia and the Americas. Probably, these megafauna disappeared because of hunting by humansone and 2.

Then, between about v,000 and 500 years ago people discovered and settled oceanic islands3. This resulted in extinction of whatever megafauna lived on those islands, such as New Zealand's moa and Madagascar's giant lemurs and elephant birds. As well, many smaller vertebrates succumbed to the combined pressures of hunting, forest removal, and impacts of conflicting species transported by voyaging people; presumably there were extinctions of other components of biodiversity every bit well, but these are not every bit well known. Because of the remarkable distinctiveness of biodiversity on islands this second wave of extinctions accounted for a great many species. For example, more than 100 endemic mammal species disappeared from the Caribbean islands alone3, and human occupation of Pacific Islands resulted in extinction of at least 1,000 bird species, around x% of all the world's birds4.

Since 1500 CE a third and still greater moving ridge of extinction has been growing. This third wave is existence driven ultimately by growth of the global human population, increased consumption of natural resources, and globalization. It is affecting a wider range of animals and plants than the preceding ii extinction waves, in the oceans too equally on countryv. Our knowledge of which species have gone extinct since 1500 is collated in the IUCN Red List6 and is nigh complete for vertebrates, particularly birds, mammals and amphibians: 711 vertebrates are known or presumed extinct since 1500, including 181 birds, 113 mammals and 171 amphibians6. Nosotros know of almost 600 extinctions each of invertebratessix and plantsvii since 1500, but given limited bones cognition, survey, and assessment of conservation status, the true magnitude of losses in these groups is sure to be far college.

2. Accelerating extinction rates

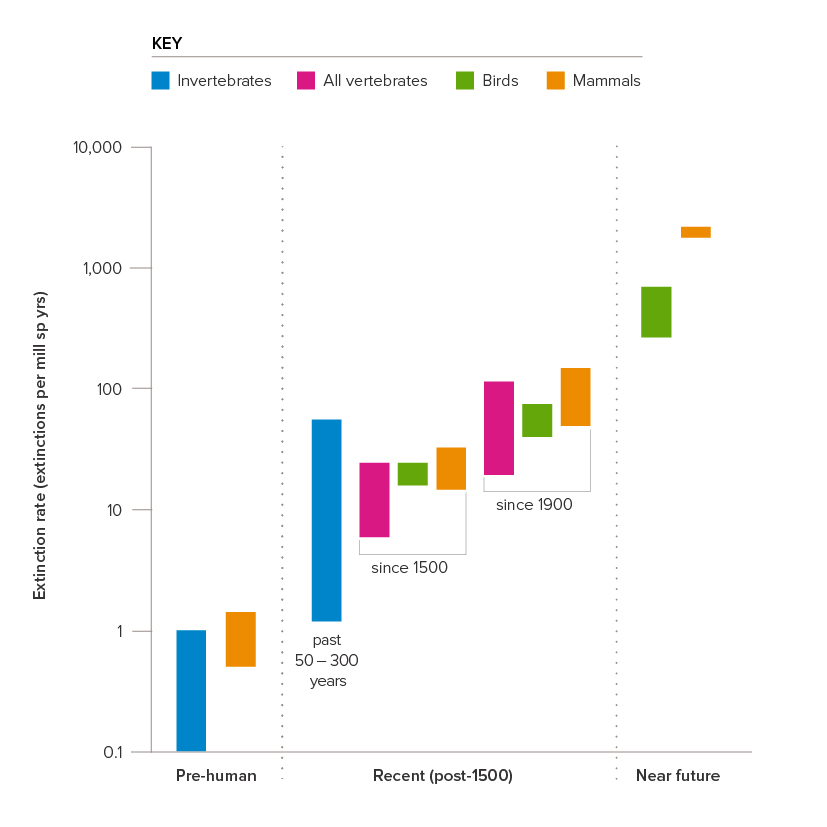

The list of known contempo extinctions is notwithstanding only a modest fraction of all species on the planet. For example, the tally of bird extinctions since 1500 amounts to 1.six% of all bird species that were living in 1500; the figures for mammals and amphibians are 1.ix% and 2.one% respectively. What is more than concerning than the raw numbers of extinctions is that they represent a rate of extinction far in a higher place pre-man levels. The extinction rate for any group of organisms is expressed as the number of extinctions that would occur each year among a million speciesviii (or equivalently, the number that would occur in a century among 10,000 species). Standardizing rates in this way allows comparing of extinction rates in different groups of organisms and time periods. Our best estimates advise that extinction rates in the recent past have been running 100 or more times faster than in pre-human times8 and 9, and that the pace of extinction has accelerated over the last few centuries (Figure one10 and 11). If this continues, the loss of species volition soon corporeality to a large fraction of all species on the planet.

Figure ane. Estimated extinction rates in diverse animate being groups through time, expressed every bit extinctions per one thousand thousand species per yr. The summit of each bar represents the range of estimates. Pre-human extinction rates are inferred from the fossil record, contempo values from documented extinctions in selected groups, and near-future extinctions are projected from the electric current rates at which species are transitioning between IUCN categories (information from refs 2, nine, x, 12 and 13).

At that place are two reasons to think that the extinction rate is nigh to rise still further. The starting time is that current levels of threat of extinction indicate a steep increment in the number of extinctions over the next few decades.

In those groups of plants and animals that take been systematically assessed under IUCN Red List criteria, the proportions classified as threatened with extinction (that is, Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable) are typically loftier, about 25% on average6, xi and 14. This effigy implies that a full of approximately one million of the globe's species are currently threatened with extinction14. Five groups (mammals, birds, amphibians, corals, and cycads) have been comprehensively assessed two or more times since 1980. In all cases the reassessments evidence an increasing tendency in the proportion of species that are threatened15.

The nigh astringent category of extinction risk is Critically Endangered. To qualify for this, a species must accept some combination of very minor total population (250 adults or fewer), extremely restricted distribution (10 km2 or less), and continuing population turn down at rates high enough to guarantee extinction inside decades6. Currently six,811 species are listed every bit Critically Endangered (of a total of 120,372 that have been formally assessed, a number all the same far short of the estimated two million-plus species then far described).

In short, the threat of extinction is now so widespread, and and so many species stand on the brink of extinction, it is articulate we could be about to lose many more than. Even if the time to come brought aught worse than the extinction of a significant proportion of all species at present listed equally Critically Endangered, that would amount to a very large increase in the total number of extinctions since 1500 CE. Because population size is still decreasing in most Critically Endangered species11 we must consider it likely that many of them will soon be gone.

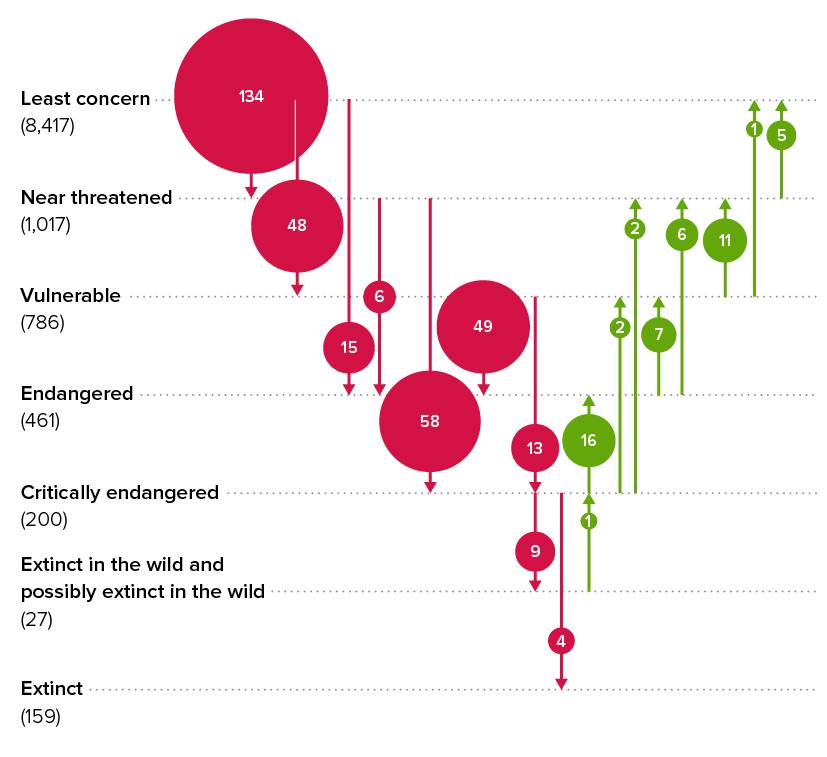

The near-future rate of extinction depends not just on current levels of threat, just on the speed with which now-threatened species decline all the way to extinction; it depends also on the rate at which species non currently threatened get and so, and how apace they and so travel the total path to extinction. These dynamics of extinction risk are unknown for almost groups, but they can exist described for a few. The best-studied case is the worlds' birds, illustrated in Figure 2.

Between 1988 and 2016 a large accomplice of bird species travelled all the way from being Near Threatened (that is, secure, but within sight of 1 of the markers of Vulnerable) to Critically Endangered (Figure 2). At the same time more than twice equally many species joined the ranks of Near Threatened from Least Concern (that is, at minimal risk) and could soon follow the others on the path towards extinction. Some other large cohort moved from Least Concern to Vulnerable or Endangered, having crossed the broad territory of Near Threatened in only a few years (Figure ii). The speed of these recent movements from low to loftier risk suggests that the number of bird extinctions is about to increase much more dramatically than might be suggested by the rather small rise in overall pct of species listed every bit threatened (from 12.half dozen% to 13.v% between 1988 and 2016).

Figure ii. Changes of Red Listing categories for bird species from 1988 to 2016. Numbers of taxa making each modify are shown in the circles. Total birds in each category in 2016 are shown in parentheses; the total for extinctions is the number confirmed since 1500 CE. Data from the IUCN Red List, as compiled by Monroe et al 201912.

Recent studies of birds12 and 13 and mammals2 have used data like that shown in Effigy ii to gauge transition probabilities between IUCN Red Listing categories (in both directions, for the better or worse) and forecast rates of extinction over the coming decades. These studies propose that extinction rates for birds and mammals are about to increase by more than than tenfold (Figure 1). Similar accelerations in extinction are likely for other groups that are not equally well-known; if anything, the increases could be even greater in many groups of organisms that are given less attention than birds and mammals and then are less likely to exist helped past specific conservation actions.

3. Intensifying pressure on biodiversity

The second reason to conceptualize a steep rise in extinction is that the forces that caused recent extinctions are every bit strong as ever. The primary direct causes of extinction are loss and deposition of habitats due to human use of country and sea; overexploitation of wild populations; and the impacts on populations and ecological communities of invasive conflicting species, pollution, and climate changefourteen, sixteen and 17. These direct causes are driven ultimately by demographic, economic and societal factors that increase the pressures that human populations identify on biodiversity. Most indicators of the direct and ultimate causes of biodiversity decline evidence that they are continuing to grow stronger18 and 19. There take been some improvements—most notably, the expansion of protected areas since 2000 (from 10% to 15% of the land surface of the globe, and 3% to seven% of the oceans) and a recent fall in the (even so substantial) global rate of deforestationxviii —merely they are likewise pocket-size to offset the full general increase in pressure level.

There are several other reasons to call up that the pressures that have caused extinction in the recent past will accept worse effects in the future. Populations of many species are condign smaller and more than geographically restricted, whether or not those species yet authorize as threatened15. This makes them more than susceptible to threats they might have resisted when abundant and widespread, considering for each population affected past some insult such every bit habitat loss or overexploitation at that place are fewer others to beginning local declines and supply immigrants to furnish losses. Also, the full general increase in human impact on nature makes it more probable that remaining natural areas are subject to several different threats at the same time, leading to compounding or synergistic effects with greater total touch20.

The future will too bring an increasingly of import overlay of global climate change to the long-standing forces of habitat loss, overexploitation, so on. The most meaning effect of climatic change may well exist to increase the frequency or magnitude of extreme events. These include many that recent experience shows take bully potential to damage biodiversity, such every bit intense tropical cyclones, marine heat waves, and El Niño and La Niña events21. Farthermost events that bear on big areas can force big, abrupt and unexpected declines of many species at 1 time.

The climate-driven fires that recently burned much of southern Australia supply an illustration of such an extreme event22. During the 2019/20 fire season, 97 000 km2 of southern Australian woodlands, forests and associated habitats were burnt past fires of exceptional intensity. The fires acquired extreme damage to habitats that typically feel recurrent fires of lower intensity and extent, while consuming other habitats that unremarkably practice not burn at all. In the broad region affected past the fires, 243 vertebrate species or subspecies are listed every bit threatened. Fires overlapped significant portions (>10%) of the ranges of 46 of these threatened vertebrates. Some had most of their habitat burnt, for example 82% for the long-footed potoroo Potorous longipes and 98% for the Kangaroo Isle dunnart Sminthopsis griseoventer aitkeni. Another 49 vertebrates not currently listed as threatened had 30% or more of their habitat burned, 100% in the example of Kate's leaf-tailed gecko Saltuarius kateae. It is possible that many currently listed vertebrates will motility into more astringent threat categories, while re-assessment of previously secure species could run across the total number of threatened vertebrates in Australia increase by xiv%, equally a upshot of this single event22. At this phase in that location is less complete noesis of impacts on other species, but rapid appraisals accept identified 191 invertebrate and 486 constitute species every bit potentially severely affected23.

4. Loss of abundance

The effigy of 25% of all species threatened with extinction is i measure out of a more full general pass up of populations of wild species. Analysis of aggregated data on population trends of vertebrates from around the earth indicates a general decline in abundance of 68% between 1970 and 2016, due both to extirpation of local populations and reduced numbers in those that remain. Roughly similar trends have occurred in most major regions of the world, in freshwater and dryland ecosystems, and in the oceans too as on landv, 15 and 24. There is besides growing evidence of widespread decline in the abundance of invertebrates, especially insects15 and 25. This is all-time studied in Europe, where information technology is becoming clear that the abundance and diversity of arthropods is declining even in relatively undisturbed habitats, evidently because of spill-over effects from agronomical state utilize26.

Then far, conservation action has had lilliputian success in reversing the full general decline in abundance of wild species. We accept prevented some extinctions; for example, interventions betwixt 1993 and 2020 prevented 21-32 bird and 7-sixteen mammal extinctions, such that extinction rates in both groups would otherwise have been 2.9-iv.2 times higher27. This is encouraging, but most improvements have been in moving species out of the Critically Endangered category into Endangered (Figure two), that is, holding the line against extinction for some of the almost severely threatened taxa. Few threatened species have recovered their original distribution and abundance confronting the much stronger tide running in the other direction (Figure 2).

Image caption: the Critically Endangered orangish-bellied parrot Neophema chrysogaster by Tiana Pirtle.

Not all species are being forced into decline; some are becoming more abundant as a result of man disturbance. In general, however, big-bodied and ecologically specialised species are more than likely to decline28, being replaced by less various sets of species that either tolerate disturbance or do good from information technology and are capable of invading new or altered habitats29 and 30. The result of this process is that a great role of the original diverseness of nature is being lost from much of the planet. As this happens, ecological communities are being made simpler and some important ecosystem functions are degrading.

5. Species extinction and ecosystem refuse

In the places that still accept them, very large herbivores such as elephants and rhinos command the construction and pattern of vegetation, promote habitat heterogeneity, limit the extent of wildfire, transport nutrients, and disperse seeds. These diverse effects combine to promote diversity among smaller animate being and establish species; megaherbivores could even influence the climate through alterations to land-surface albedo31. The wholesale extinction of mega-herbivores many thousands of years agone damaged ecosystems and diminished biodiversity in ways that are only outset to exist understood31, 32 and 33. Big predators as well sustain biodiversity and stabilize ecosystems by regulating populations of smaller predators and intermediate-sized herbivores34.

Amongst living mammals, amphibians, birds, reptiles and fish, the very largest species go on to be at highest hazard of extinction: 59% of living megafauna are threatened, and 70% are decreasing in numbers35. The threat of extinction is also exceptionally loftier amidst the smallest vertebrates36. That is, human affect is deleting the smallest and largest vertebrates, and thereby circumscribed survivors to a narrower size-range than was produced by evolution.

This is 1 instance of a more than widespread miracle, in which homo bear on reduces the diversity and range of traits of organisms in natural assemblages28. The full general result is a reduction of functional diverseness too every bit total numbers of species, simplification of ecosystems, and in consequence loss or destabilisation of of import ecosystem functions. So, for example in forest and woodland ecosystems the loss of mega-herbivores tin can upshot in college incidence of destructive wildfire37; in the oceans the loss of large species is reducing connectivity among ecosystems and thereby making them unstable5; and declining diversity of insects diminishes many essential ecosystem functions such as pollination and nutrient re-cycling15.

vi. Conclusions

Our knowledge of past and time to come extinction rates makes it clear that the problem of extinction is urgent. The problem has two main components. Commencement, the extinction of species is reducing the total diversity of life on the planet. Although the extinction tally does not yet represent a large proportion of all species, it is substantial and ecologically important. The rate of extinction is ascension fast, and on current trends a large fraction of all the earth's species could soon be gone. Second, the combination of extinction of some species and declining abundance of many others is causing a general loss of affluence and diversity of wild species and compromising the functioning of ecosystems.

The highest priority for activeness should be the prevention of extinction, because the extinction of any species is an irredeemable loss9. Science-based interventions have a adept record in saving species from extinction and recent losses would have been significantly worse without them27 and 38. The actions that have been most consistently successful are institution of protected areas, habitat restoration, and intensive management of modest populations including reintroduction27. The reason that nosotros take not seen more than success is primarily that investment in and resourcing of species conservation is in full general far likewise low39.

The trouble of preventing broader decline of wild species requires more circuitous solutions, based on retention of large areas of intact habitat together with rewilding of degraded areas, improvements in the sustainability of exploitation of wild populations, development of strategies for reducing the impacts of invasive species at landscape scales, and mitigation of climate change. Accomplishing these changes will require transformations of the relationship of human being communities to nature that will depend on the application of science, development of new socio-economical and governance models, and restoration of ethnic knowledge and practices of environmental direction13, 15 and 26.

Source: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/biodiversity/decline-and-extinction/

Posted by: bordeauxhaptand1963.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Animals Are Lost To Loss Of Habitat Last 25 Years"

Post a Comment